Kings Park Psychiatric Center, NY

- jonathananeary

- Jul 6, 2022

- 22 min read

Updated: Jul 11, 2022

“The vandals made a mess of things,

And the homeless just walked right in,

Well, they worked here once and they live here now,

But they might work here again,

The ordinary people…”

-Neil Young

You’re five stories above a crumbling assortment of abandoned bricks, concrete, asbestos, and rusted steel, when the roof beneath your boots starts to cave. The blanket of gravel and black rubber is spongy at best, and deadly on a bad day – a really bad day. You’re the reason for the chain link fences, the “No Trespassing” signs, the plywood boards across the doorways, and the four separate law enforcement agencies who parade around like prison guards on patrol; you’re the liability the State of New York desperately wants to avoid. For a moment you wonder why you’re stupid enough to be clambering through broken windows and climbing atop forsaken elevator shafts – your work gloves and camera bag caked in toxic white dust – but then you see the view of the courtyard. This place is a haunted playground, a neglected treasure trove of controversial history, where you escape to in order to fill a void in your heart, and attach meaning to the abandonment in your soul.

It was a crisp May morning in 2016 when I first laid eyes on the former Kings Park Psychiatric Center with an assortment of fellow explorers who didn’t otherwise spend a lot of time together. I rolled up in my little Honda Civic with Tyler, a fearless childhood friend who lived down the street from me, Sam, a recurring partner-in-crime on my travels, and Z, an acquaintance from high school who wanted to cosplay as Harley Quinn at our first real-life “Arkam Asylum.” Sam and Tyler were cousins, but I hung out with them for very different reasons on separate occasions, and none of us spent much time with Z with except for these excursions. While a small town omits the term “stranger” from your vocabulary, it’s funny how urban exploration draws people closer together, and establishes a team mentality by the time you’ve finished your gas station coffee and slung a backpack worth of gear over your shoulder.

After a couple of hours on the road, we had reached what is known today as Nissequogue River State Park, which encompasses the hospital complex like many other state-asylum-turned-conservation-oddities in the Northeast. With spectacular dramatic flare, the most accessible parking lot was directly in front of a show-stopping architectural formation known as Building 93 – one of the most iconic structures at the facility: a 13-story behemoth built in 1939, and used as a backdrop for a handful of films, including “Eyes Beyond Seeing,” and “Peripheral Vision.” It was certainly a mesmerizing masterpiece, designed by William E. Haggard, that served as a reaffirming ambassador to the grounds. We gawked and took the scene in, before shuffling toward it in amazed unison; even with our different backgrounds, we were definitely in this together.

Despite being beckoned by the monstrosity, we were able to break its spell long enough to formulate a more cautious plan of execution. After a quick discussion, we elected to bypass it for the Laundry Building – dubbed “94” – which was off to the side, and more secluded from prying eyes. Wandering its grounds beforehand gave an opportunity to observe from a distance, which is a good rule of thumb for these expeditions. An hour of scoping things out lets one watch and listen for suspicious activity, other groups, and most importantly: police and security patrols. Rushing into things too hastily can put you into a sticky situation, and the more reconnaissance the better.

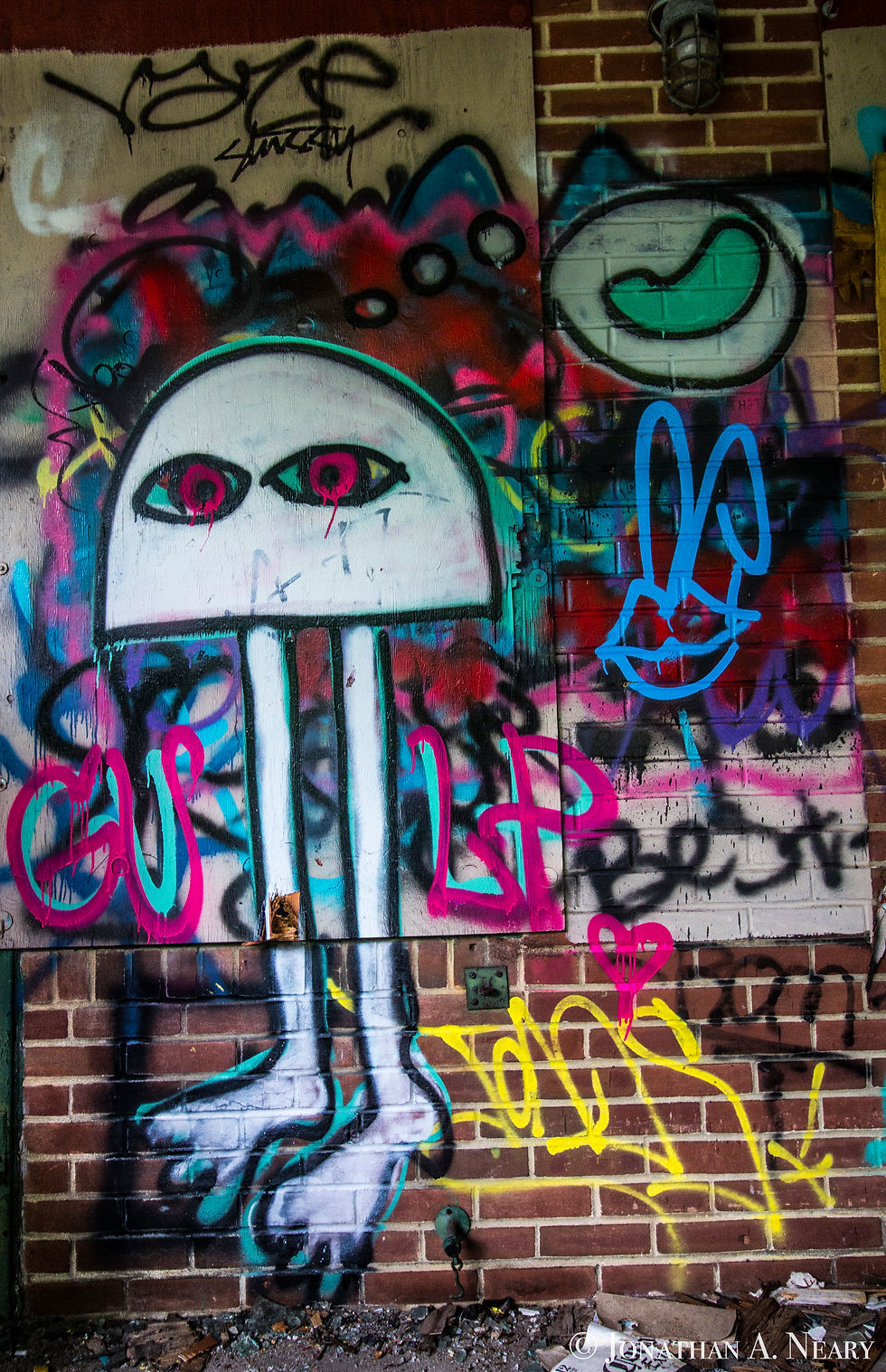

Built in 1953, the most accessible portion of Building 94 was the loading dock, which was adorned with vibrant graffiti and limited passage into the halls of the massive laundromat. A year after its inception – in 1954 – the psychiatric center reached its peak occupancy of 9,300 people, and “94” was responsible for washing all the clothes and bedding. According to author John Lazzaro, this amounted to 170,000 lbs of laundry each week, operated by patients and overseen by only 12 employees.

Like most of the operations here, staffing was inadequate in retrospect, but employment was sought after not just within the hamlet that was built around the hospital, but across the country from recruitment efforts that often toured the South. Staff were salaried and offered room and board; amenities like gyms, tennis courts, and mini-golf courses were enjoyed by the entire community, with local residents often strolling and riding bikes through the grounds. A boat basin even provided mooring to seafaring employees, with access to the Long Island Sound, just a stone’s throw from the Atlantic Ocean and the shores of New England.

The glimmering ceramic-coated blocks housed unhinged doors, empty gallons of cleaning solution, and a teal-painted table slapped with an “Infectious Waste” label. Z posed for a few shots with her baseball bat, and we all marveled at her ability to explore in high heeled prop shoes; thankfully she packed a couple of pairs. The loading dock was the perfect stage for our performance, and I snapped a few pictures of Tyler sporting his infamous lack-of-a-smile for the camera. This got us into the spirit of exploration, almost causing us to let our guard down, but by now enough time had passed to put at least some of our anxiety at ease. It was almost showtime; we were ready to make our way back to Building 93, circling like giddy vultures as we scouted out an entrance.

Stripped and peeling apart, the plywood over the rear entrance at the center of the building offered enough of a hole for us to shimmy through. Normally I wouldn’t advertise highways and openings, but years have passed and routine maintenance has most likely patched this point-of-entry multiple times since. Awaiting us on the other side was a hallway worth of trashed chambers sporting hospital furniture and collapsing ceilings, and the occasional “dungeon” lacking windows or any other source of natural light. Passing through a large corridor – which seemed to house the amenities for a cafeteria of sorts – we entered a quasi-basement-level graveyard of beds. It turns out that the building was an infirmary for geriatric patients, as well as a drug treatment center.

Stacked like legos that omitted more and more bricks the taller the tower reached, the building had a progressively wider footprint toward the basement. Subsequently, the patients requiring more exercise were assigned to the lower floors, which offered increased opportunities to work on mobility, but once occupancy began to trend downwards in the 1970s, the building also saw the most rapid decline of use, starting with the upper levels closing until the doors were permanently locked in 1996.

The great shuttering of psychiatric centers was controversial at the time, and seemed to hit the Northeastern United States in a colossal wave in the early 1990s, roughly a century after their inception. While the 19th Century’s overpacked asylums posed a serious problem in urban areas, i.e. New York City and its future boroughs, the remedy came with issues of its own. Kings Park, it’s worth noting, gets its name from King’s County, also known as Brooklyn, while alluding to a more “outdoorsy” establishment. Similarly, Harlem Valley Psychiatric Center was built to replace Manhattan’s facilities in upstate New York, which was the first place to captivate my imagination as a toddler during my youth living in rural Connecticut. Initially designed to provide a “farm-like” atmosphere, offering fresh air and agricultural labor, with less crowded conditions, the rapid advancement in care came at a price – literally and figuratively.

Some of the cutting-edge procedures during the life of these institutions turned out to be inhumane by today’s standards. Lobotomies, for example, sever connections in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, rendering many recipients “vegetables,” and incapable of ever functioning in society as “normal” human beings again. The process cannot be reversed, and while the operation did in fact eliminate violent tendencies in several cases, it was often administered to people suffering from issues that could have been resolved through less invasive treatments.

Early attempts at the procedure began 1888 with Swiss doctor Gottlieb Burckhardt, who theorized that deliberately creating lesions on the brain would alter one’s behavior. After performing surgeries on six patients, he found that two saw no change in behavior, two became more passive, one showed notable improvement, and one died. Consequently, he advertised his work as having a 50% success rate, though many in the medical field were skeptical, and therapeutic nihilism still prevailed as most believed mental illness couldn’t be “cured.” John Fulton, a neuroscientist from Yale University, similarly experimented with lobectomies on two chimpanzees in the early 1930s, noting that their tantrums were replaced with pacification, during instances where rewards weren’t given for predetermined positive behavior or reactions.

Apparently intrigued and inspired by Fulton’s work, Portuguese doctor Egas Moniz performed the first “leucotomy” in 1935, drilling a hole in the skull and using alcohol to create a barrier in the fibrous white matter of the brain. When multiple injections were sometimes needed to see results, Moniz began inflicting lesions instead. While still controversial, the operation was similar to that of insulin shock therapy introduced two years prior, which used injections to induce seizures or a catatonic state, rendering its subjects docile and easier to care for. Moniz would later receive a Nobel Prize for his work in 1949, though it has since been contested.

After meeting Moniz, one of the most renowned doctors in the field – Walter Freeman – began to refine the approach, experimenting with grapefruit and an ice pick in his kitchen until he came up with his own version of the operation: the “transorbital lobotomy.” Concerned that many state hospitals lacked access to operating rooms, he omitted drilling from the process, and instead developed a method of using an “orbitalclase” to enter the brain through the eyelid, using a mallet to break through the bone along the bridge of the nose. From there the tool would be manipulated at various angles to sever the white matter, with the first trial on a live patient occurring in 1946. If anesthesia wasn’t available, electroshock therapy would be used to knock the patient unconscious first; the surgery was rapidly becoming a simple “office visit” procedure, instead of “surgery,” angering his partner James Watts, who became an advocate against the practice.

Describing a 29-year-old recipient as a “smiling, lazy and satisfactory patient with the personality of an oyster,” Freeman referred to the results as “surgically induced childhood.” He then took to the road, where he would perform an average of 25 operations a day, including 228 over two weeks in West Virginia in 1952. During this era there were a conservatively estimated 40,000 lobotomies administered in the United States alone, but as criticism mounted, Freeman would execute his final procedure in 1967, which culminated as a fatality (a far-too-common outcome), leading to him being banned from practicing in the country. A year prior to his death in 1972, he published the results of his followups with 707 schizophrenic patients, and noted that 73% of them were still dependent on hospitalization or some other form of care.

Electroshock therapy is another instance where the science was rapidly disputed in a short period after its introduction. Though it’s still practiced today in a small number of patients, the wide-ranging use of its heyday in the 1950s received criticism due to its effects on the memory and lack of consent. Furthermore, an "effective dosage" wasn't always dialed in – or calculated properly – thus the act of running electricity through one's head wasn't an exact science the way it is in modern times. There are also plenty of accounts of its use as a “punishment” by orderlies, though other unprescribed methods of discipline at KPPC included hanging patients in straight jackets on a hook on their bedroom window, or worse: asphyxiation via pillow case.

Some of these horrific accounts come from Lucy Winer, who sought to draw attention to the system’s failure after being admitted following a suicide attempt when she was 17-years-old. Initially telling her mother she was going to overdose on sleeping pills before following through with the threat, she was told upon arrival to the “psych center,” that she would be chastised for “crying,” and she spent the next couple of decades trying to survive. Her legacy lives on through the documentary “Kings Park: Stories from an American Mental Institution,” which also interviews former employees. The Smithtown Experience’s film, which also interviews members of the community on the positive impact, offers a different tale, though I’m sure there is truth in all accounts.

Perhaps the most recognizable name on the hospital’s roster was Percy Crosby, responsible for the Skippy comics of the 1920s-1940s, and inadvertently the peanut butter brand (who allegedly used the name without permission). During his third marriage, his mother’s death and his alcoholism fueled a suicide attempt, which landed him at Bellevue Hospital in 1948. His wife, who worked as a nurse, convinced him to transfer to the Kings Park Veterans Hospital, where he would spend the last 16 years of his life after being diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. It has been rumored that several of the murals in the buildings were of his own hands, along with other artwork and manuscripts.

It’s important to point out that not everyone “deserved” to be committed at these state health facilities, and that behavior such as adultery was classified as a disease, and husbands often sent cheating or hyper-sexual partners to these hospitals as a form of discipline, during eras when women were not entitled to the same rights as their male counterparts. Children were also enrolled in programs for rudimentary learning disabilities or social anxieties, and set up for a life of internment within the system. Furthermore, homeless people and immigrants who “couldn’t assimilate” were often pushed out of the public eye and hidden away at places like this. Paired with abuse from employees, this factory of nightmares churned out muckraking stories from the likes of Geraldo Rivera and other local journalists.

While we often think of these barbaric practices when we look back on the history of mental health, it’s important to also remember the advancements that left them in the past. The invention of pharmaceuticals like Thorazine and haloperidol pushed surgical and other invasive treatments to the side, and made “off-campus” therapeutics more accessible. People no longer had to live in “asylums” to get medical help, and community and home-based assistance replaced the need for gigantic institutions. This was certainly one of the catalysts that led to KPPC’s eventual demise, though nail in the coffin came from assessing the price tag of government-sponsored healthcare, which generated fears of bankruptcy with President Johnson’s introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.

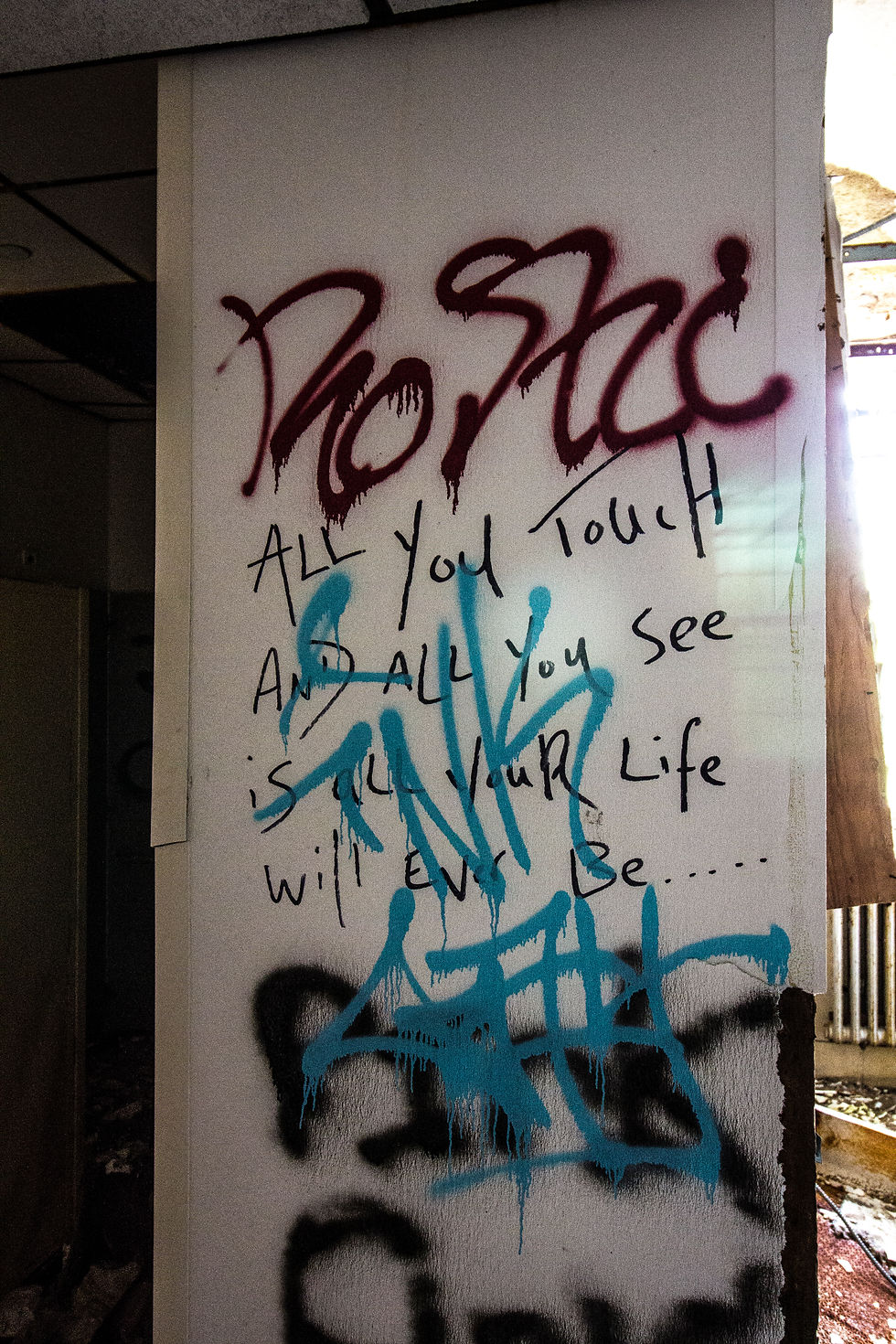

Federal coverage of mental health wasn’t provided to patients under the age of 65, and New York State became increasingly concerned with how they could afford the centers’ programs. In 1993, the New York State Community Mental Health Reinvestment Act was passed, which initiated a consolidation effort leading to the transfer of many residents to the larger Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, which is still in operation today. The remaining infirm were released into more localized programs, and Kings Park was decommissioned three years later, left to the hands of the vandals and the homeless – and explorers like us.

Despite the number of times I tip-toed through this place, I never got beyond the room littered with beds; the staircases were enticing, but we were always playing second fiddle to another “tour group,” and the eerie clanging and banging from above shooed us back out the way we came. Even if we were on a similar mission, it was better to let them draw attention to authorities than to become entangled in their shenanigans. Not to mention, the onslaught of destruction and smashing of equipment went against the "Leave No Trace" principles I've always held in both the backcountry and the abandoned. We took the time to get some more shots of Z, and I would later snap a couple of Ivory here, who was another childhood friend who took the opportunity to explore with me.

From the backside of the building lay a concrete staircase, overgrown with vines and shrubs, with a metal handrail that was all but rusted out. The parking lot below is the home to Buildings 29 & 44, the power plant and food storage, respectively. This was a common hangout for skaters, some of whom I assumed were behind the more modern murals on the property. Referring to the power plant as “Terminus,” after a reported safe-haven in “The Walking Dead,” I wouldn’t enter the building until I returned with a seasonal Irish employee later that summer.

Niall and Shane were a couple of adventurous young lads who worked at a park in Montauk, which also sported its own abandoned buildings. 20-years-old with easily-forgeable drivers licenses from the mother land, they picked up restaurant shifts in the village for decent wages, while helping me run a campground on the outer beach for housing and a work visa. By the end of summer I trusted – and enjoyed – their company enough to bring them along for a series of eccentric tours of the States. This obviously included a jaunt through Kings Park with Niall, where we picked up where I had left off, since I can never leave a leaf unturned!

One by one, we crouched and slid beneath a cage of bars at the side of the building, to witness a maze of pipes and wires, bundled like spaghetti in a fork. Controlled by various computers and an office space full of rusted filing cabinets and deteriorating pressboard desks; this place must have been quite a sight back in the day. Panels of equipment sat wide open, like rows of lockers left ajar after the final bell before summer break, surrounded by pried and hammered metal cases and concrete dust. Evidently the steam power plant once incinerated 100 tons of coal a day, and required its own rail line to keep the center running. It’s hard to believe such a place was the life-blood for over a hundred buildings at one time, but then it’s also difficult to envision thousands of people shuffling around and spending every waking breath within the confines of these bricks.

This was a massive operation, and an entire town was centered around the jobs it provided, complete with a nursing school, greenhouses, a piggery, and its own token-economy for a community store. Although the smoke stack was demolished in the early 2010s – the debris removal project was still evident upon my first visit – this place still felt like a powerhouse. Other explorers have utilized the tunnels that feed other buildings as a mechanism for travel, but my fear of asbestos and confined spaces limited my time inside. A quick peek around, while security did a drive-by just beyond where we stood, was all the thrill I needed at this stop.

As for Building 44, I would come to investigate it more thoroughly that summer. A forklift was still parked in the warehouse-like space on the Southern side of the facility, and wading through the graffitied hallways to the top floor yielded a collapsed wall that looked more like the casualty of a war-zone than a condemned hospital; I half-expected to see a tank outside. Blackened by soot and ash, much of the building had also been scorched by the flames from delinquents over recent years. The gaping hole in the wall offered a contrast between the rigid structure of the institution and the tree-infested green-scapes of an otherwise rural community on Long Island; then again this was once home to some truly impressive gardens with its own agricultural hub.

Tucked off to the side was the Maintenance & Workshop building, aka Number 5, crowned with corrugated roofing and skylights above a series of work benches. The ground was littered with nests of heavy duty cables and wiring, and dilapidated pipes were dangling from the ceiling. I wondered how many blue collar workers congregated here in the morning, drinking coffee and reading the paper, before embarking on their daily duties; I spent a lot of time in that line of work, so it resonated with me as I tried to envision it. The exposed environment beside a main thoroughfare – and the repurposed train tracks as a pedestrian/cyclist trail – made us apprehensive, however, so we didn’t doddle during my maiden voyage, and instead we made our way across the street to another gargantuan maze of 1930s brickwork.

Known as “the Quad,” buildings 41, 42, and 43 connected to comprise an intricate fortress. From the sky, the central building is laid out like an “X,” with “H” shaped buildings above and below it, each with two “fingers” jutting out on either side. This results is two courtyards toward the center of the structure, entirely sealed from the outside world. Built to house geriatric patients between 1932 and 1933, it predates "93" by a few years, which may note the change in building upwards instead of outwards for expansion. To access the building, we crossed an active two-lane road and headed up a walkway between a sea of tall grass and weeds. The sheer size of the structure made for a challenge worth conquering, and we began circling the grounds in anticipation immediately.

After a few minutes of snooping around the outside, we found our way in through a stairwell, which lead to a plethora of vacant rooms painted white and green, and an old scale rusting into oblivion. I wondered if it would be more forgiving than the one in my doctor’s office, but feared that standing on it would break some spring or measurement device, and I would rather see it preserved than having met its demise underneath me. Pink arrows blazed the doors and hallways, and once again I felt like we were on some crazy self-guided tour of a forgotten relic. Each slab of concrete made an excellent canvas for graffiti artists, and we passed mural after mural as we made our way upwards, finally reaching a set of elevators with ladder-like steps that came down from a hatch in the ceiling. While we didn’t know where “there” was, it was obvious that we had nearly reached it, and so we climbed atop the elevator shaft, gaining access to the roof – yes, that roof.

The views of the courtyard were spectacular, and the fresh air was a welcome relief from the stagnant haze of God-knows-what we had been breathing on the inside. Z popped some bubblegum in her mouth and leaned against the wall that housed the elevator shaft, posing for shot, as I nervously shifted my weight over the spongy gravel and rubber. Some spots felt safer than others, and the further we ventured, the more evident the damage became, with portions of the roof missing entirely as we gazed upon the hallways below. This didn’t phase Tyler, and when the only path forward became a single steel beam, he cracked open a Twisted Tea he had stored in his pocket, and sauntered across it like he was a veteran acrobat on a low-hanging tightrope.

I had really come to enjoy our team; each of us had a strength the other could build upon. Tyler was the wild card who kept us moving forward, Sam was the pessimistic-yet-curious soul who looked at the world as a puzzle to be solved, Z was the actress who found character amidst the splendid setting, and I was the photographer who saw darkness as a subject to be captured. Furthermore, each of us was a set of eyes and ears to look out for a common enemy, and our survival and criminal record depended on one another for survival. “Urbex,” short for “Urban Exploration,” was a dangerous sport, but when things are going well, you tend to appreciate the comeraderie of those you do it with.

While my first experience ended here at the Quad, I would also return a year later to traverse Buildings 7, 21, and 22: the last facilities in operation. During my visits I would see the before and after of the burning of the infamous “cube” – a square-shaped water tower perched atop the roof of Number 7 – which devastated the exploring community. Being closest to town, the cluster of structures was one of the hardest hit by vandalism in the years following the massive closure, and its subsequent popularity meant that I often witnessed squad cars parked out front. While everything here is a game of cat and mouse, the felines definitely kept watch over this “buffet” of photo-ops, and I was a hungry rodent.

Built in 1957, Buildings 21 and 22 were used for later admissions to the center, and were connected via walkways – built like aboveground tunnels – to Building 7, which finished construction in 1966, and operated as a surgical and administrative office building until the very end. This was the first time I noticed bus stops on my tour, and I couldn’t imagine waiting for public transit here; I’m sure a shuttle beat walking the grounds every day like we had been doing. I wondered when the last bus ran, and where the final patients would go when everything closed down. “Pilgrim State” was only an eleven minute drive away, which I would visit as a bonus stop on a tour with my best friends Linda and JB in January of 2017. Pausing for some selfies, it’s one of the few times I entrusted my camera to someone else, allowing Linda to snap a shot of me standing in the tower doorway. While most of the inactive buildings at Pilgrim were demolished, the “tower” still loomed above the Long Island Expressway; but that’s another story.

These later excursions also included a couple of trips into Building 37, which provided an on-site staff dormitory. One such visit was with my lifelong friend Chris, who knew the best way to celebrate my birthday was to spend the afternoon in an abandoned building with a camera. Another trip was with Whitey, one of the most original people to have ever crossed paths with me. Come to think of it, JB’s birthday was also celebrated here, if that tells you anything about my inner circle. Sinks and light fixtures had long since succumbed to gravity – with the help of local kids, I'm sure – and damp sections of the walls were peeling lead paint in hefty sheets. We dipped in and out of doorways, stopping for a snack at an outdoor patio behind the dorms, where I would joke that the service was abhorrent despite the hauntingly beautiful ambience.

Off to the side was a barn-shaped garden shed, which imparted the wisdom of “peace, love, dinero.” I suppose that none of this would have been possible without gas money – and gear certainly wasn’t cheap – but the decay of man by the force of nature brought a great deal of peace to my soul, making it all worth it. After all, sometimes the old ways are the best ways, and Mother Earth often corrects the errs of society, by wiping the slate clean and rebuilding from the ground up.

I suppose my love of these all-but-forgotten places started when I was 10-years-old, when I wandered the halls of a 1920’s era Gatsby-esque mansion that was slated for demolition. I didn’t possess the photography equipment to capture it in my youth, but since then my infatuation has only grown stronger, and now I rarely travel without a camera. History can be elusive if we’re not careful to preserve it, and being able to seize the moments when a heavy door slams shut, provides me with a sense of purpose, if only within myself. While we will all turn to dust some day, each and every one of us has the opportunity to leave behind a legacy, through the stories and memories we share with one another.

My birthday trip was memorable for another reason, however, as it was the first time I had to interact with law enforcement on these ventures; yes, the mouse was in the trap, but it was easy enough to wiggle out from, this time. Coming across a local officer on the street, as I snapped a few shots of the flowers taking over some tagged up signage, I luckily had a plan in place. Swapping memory cards between outdoor and indoor shoots, and hiding the indoor cards somewhere inconspicuous, I was able to “prove” that I was only interested in the exterior, and had not been trespassing that day.

Exchanging tales about having to play the cat at my own park out East – where I was responsible for securing WWII and Cold War era structures – we actually hit it off quite well. Though I didn’t carry cuffs or a badge in my line of work, I did have rules to enforce, culpability to evade, and properties to protect from delinquents and arsonists. Stating he was “too old and fat to go chasing people through the buildings,” the cop declared he wouldn’t dare enter the facility, even if someone fell and broke their leg; “I’ll be outside waiting for you, otherwise you’re on your own.” It makes sense that those who patrol these grounds have figured out a more effective method: waiting until sundown to catch explorers exiting the buildings and returning to their cars. Minimum effort, and maximum results; photographer and vandal beware.

On the Eastern side of the property, a series of small houses stood in remembrance of the doctors who once ran this place. Split homes and brick cottages with payphones – useless artifacts by this day and age – sat in a row among a field of bent grass and a dusting of snow on our January jaunt. Once-upon-a-time these were perks of the job, but being owned by the state instead of the occupants meant that when the closure came about, the residents had to find somewhere else to live, though with substantially more opportunities to resettle than their patients. I hoped the more sinister people had to accept jobs in landlocked Ohio, or somewhere that didn’t offer the same benefits as Kings Park, but karma is a fickle mistress. Otherwise, I felt a similar sense of sadness for the working class and compassionate caregivers; this was more than a livelihood – it was their community, their family, their whole world.

I did wonder, however, if patients or staff squatted here after 1996 – a reality not unheard of during this time period. In fact, the notorious real-life “Cropsey” of Staten Island had camped on the grounds of Willowbrook State School, which has a similar story to that of Kings Park. For those not in the know of this New York urban legend, Cropsey was a “boogeyman” of sorts, who preyed on kids in the city. In real life, however, Andre Rand: a former custodian, orderly, and physical therapist at Willowbrook, lived in the woods outside the facility and abducted and murdered multiple children, who often exhibited some form of mental disability. At least one body was found on the property, and it’s suspected that others could be buried there as well. This was also the specific location for Geraldo’s career-changing exposé, after being invited by an employee to witness the conditions of a state-run medical center.

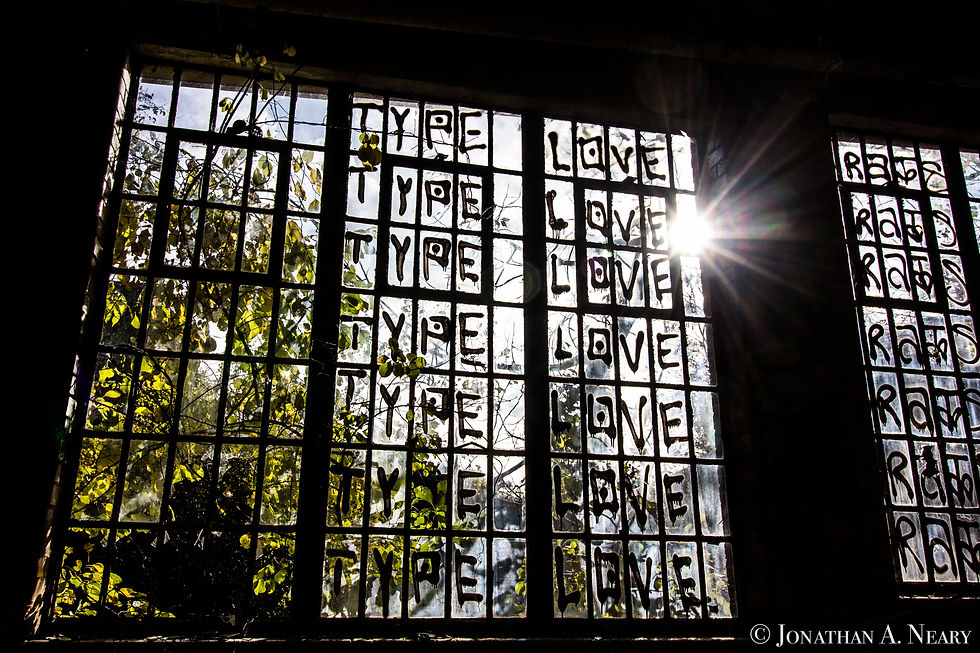

Further East still, opposite the parking entrance that lies beneath Building 93, sits a more occupied section of the park. Complete with a fleet of state vehicles, a security booth for collecting recreation fees, and a plethora of upper-middle-class dog walkers, this chunk of land hosted the last trip I took to the place before moving out of state. The vibes felt vastly different at Buildings 40, 122, 123, and 124; perhaps it was additional eyes, or maybe the times were changing – either way I was increasingly on edge. Regardless, we came across a hallway decorated with the reminder to “love,” almost indefinitely, as the letters spanned pane after pane of glass into the waning sun’s oblivion, and the magic was restored.

Gazing upon a series of plywood window covers, I was smitten with the more recent artistic contributions of the neighborhood: painted murals, stemming from a school project by local students. It was evident that the next generation was becoming stewards of this historic place, while subsequently influencing its future. Though none of these composers possessed the notoriety of Percy Crosby, something just as beautiful was being built: the bridge between the times and tenses, and the evolution of a community. I wondered what conversations were struck by engaging a classroom of curious souls, and what impact they might have on the world moving forward; it was clear that a new legacy was being left here.

Kings Park Psychiatric Center may have seen many golden ages: the crowded asylums of the 1800s transitioning to farmlands, the birth and death of psychosurgery, the breakthroughs of pharmaceutical antipsychotics, and the conversion of mass incarceration to the individualized community-based treatment of manageable mental illness. For me it was the golden age of Urban Exploration, with a playground offering something fascinating for all walks of life – rich in history, architecture, artwork, and tangible relics somewhat frozen in time. Furthermore, it was unequivocally inspiring – not just in photography and urban legends – but in philosophy, and the necessity of asking difficult questions of society.

Today, the majority of mental health care is under the purview of prisons and jail cells, with cities and states relegating the issues of illness and drug addiction to broken justice systems across the nation. Walk through any downtown of America’s inner-cities, and you'll see the forsaken ones: the folks who would have been committed to places like KPPC in the years prior. Are they better off now than before? Is the prevalence of fentanyl-laced heroin an acceptable replacement for Thorazine, and does the reintroduction of nihilistic disregard suit a society ripe with financial excess? Some of us pride ourselves in being empathetic to those experiencing “houselessness,” but many of the “tent cities” that make the headlines of the local paper are not people “down on their luck,” but citizens fighting trauma and demons that socks and sandwiches cannot quell.

To dole out the necessities for a civilized quality of life, without addressing the impact of opiates and afflictions, is to do nothing more than merely delay a death sentence. At the end of the day, are we better off now than we were in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, during the heyday of institutions like Kings Park? Perhaps time will tell, and only you can be the judge, as a voting constituent of a leading first world nation. The power of change rests in your hands, and we as a society need to forge ahead together – using science, compassion, and policy advocation. In the meantime, this explorer will be using his camera to document the past, as a means to discuss how we can do better in the future. What legacy will you leave behind?

Comments